I find much of dating discussion online to be mindlessly banal. Intellectual gymnastics attempting to reduce human passions into logical frameworks. Maybe it’s driven by the dating app culture that has devolved things into a nerdy game of scores, swiping, and ticking checkboxes. In the physical world, such trifles as “muh bodycount” are irrelevant when caught in a fit of lust.

Also lost in the sauce is the potential for incomprehensible appeal. The rare aura that some possess to ensnare potential mates. They may not be the most beautiful, but their way of being just exudes sexual energy. Such was the case of Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

“Russia is a very large lunatic asylum. If you visit an asylum on an open day you may not realize you are in one. It looks normal enough, but the inmates are all mad.” - Zinaida Gippius, 1916

Born in 1889 in the outskirts of then Russian occupied Odessa, Akhmatova settled in St. Petersburg as a young woman in the 1910s. Like many poets of her time, she frequented the hazy, drunken, underground haunts where artists performed and intellectuals would congregate.

In contrast to the salons of Paris, the scene of St. Petersburg was one of nihilistic decadence that prevailed during the dying days of the Romanov dynasty. Anna’s poems read like a pre-cursor to some of the self-destructive, sexual, sadgirl music that is prevalent today. Crowds would gather round to hear her sing verses of despair in smoky lounges.

Here we’re all drunkards and whores, Joylessly stuck together! On the walls, birds and flowers Pine for the clouds and air. The smoke from your black pipe Makes strange vapours rise. The skirt I wear is tight, Revealing my slim thighs.

“Inexplicable Sudden Appeal”

Although married and with child, Anna was noted for her incredible magnetism with men and had several affairs. Her estranged first husband protested “that woman is a witch, not a wife."

Looking at depictions of her from that era, one would not immediately think this was a beauty icon. Even in photos of her youth she has a resemblance to the “old hag” half of the famous young girl/old lady illusion. But, many men described some sort of irresistible aura which she carried.

Gregory Adamovitch (a fellow Russian poet) remembered: "when people recall her today, they sometimes say she was beautiful. She was not, but she was more than beautiful, she was better than beautiful. I have never seen a woman whose expressiveness, genuine unworldliness and inexplicable sudden appeal set her apart anywhere and among beautiful women everywhere.”

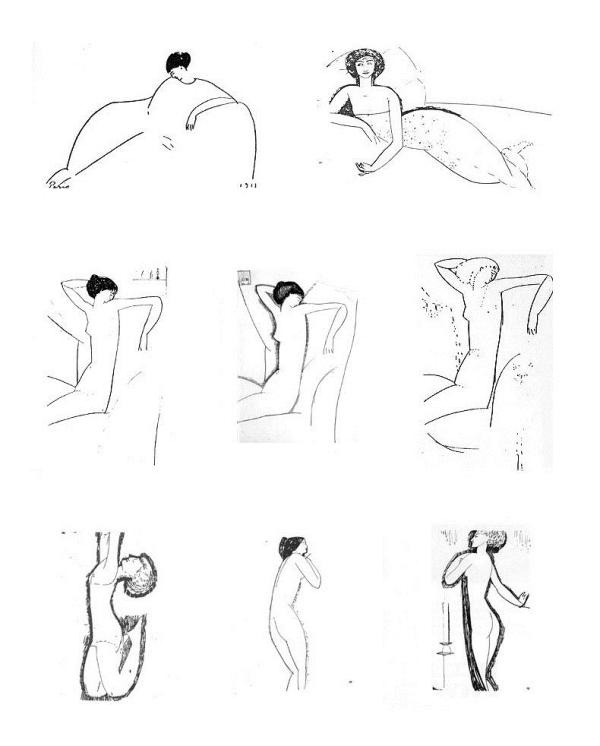

He was not alone in his sentiments. While on honeymoon with her husband in France, Akhmatova met the Italian painter Modigliani. The painter became so fixated on her that a year later when Anna briefly fled to Paris they had a lengthy affair. In this period Modigliani produced countless portraits and sketches of her.

It was not just Modigliani, many artists sought out Akhmatova to sit for portraits. She became a preeminent muse of Russia.

Revolution and Suppression

When the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, folks in Petersburg were faced with the decision to flee the country or remain. While many left, Akhmatova chose to stay and weather the coming decades of terror.

The changing Soviet regimes had little use for the writings of a tortured poet. She continued to compose works for decades, but few were published. Her emotional depictions of youth transformed into laments of the horrors witnessed under communism. Family members executed, her son spending years exiled in the gulags.

Only in the late 1950s, when Khrushchev came to power did Akhmatova begin to gain good standing again and recognition within Russia. Aged and weary, the babushka offered a last toast to her homeland.

Last Toast

I drink to our ruined house

To the evil of my life

To our loneliness together

And I drink to you—

To the lying lips that have betrayed us,

To the dead-cold eyes,

To the fact that the world is brutal and coarse

To the fact that God did not save us.

That last poem in its original form (Russian) is absolutely brutal, especially if the reader understands the nuances of old Soviet-era (and before it) life from Russian culture.